Language of the Records

In 1563, at the Council of Trent, the Church authorized that the parish priest was to keep records of Baptism and Marriage. In 1614, a directive called for Death records to be maintained as well. Roman Catholic records were kept in Latin, while the Greek Catholic records were kept in Old Church Slavic. The records are extremely basic and do not hold much information. The researcher should begin with the latest records as possible, as mid to late 19th Century records often begin to have a greater detail, such as mother’s maiden name and grandparents of the birth child or newlyweds.) For baptismal records, often only the father’s and mother’s name is given with only the father’s surname. this makes for difficult identification since there can be multiple people with the same first and last names living in the village, even the same exact age! Short after the Austro-Hungarian Empire took control of the region, records were to be formalized and written in Latin. However, disturbing as this might sound to today’s nationalist Pole, Ukrainian, Rusyn, Slovak or Czech, at the time of the edict, Latin was considered the lingua franca of the Christian Empire. Also, keep in mind that the idea of nationality was of little importance to the peasant at that early time. In addition to Latin, you may find the priest included some Polish and Ukrainian. And for the genealogist, this makes for easier research as compared to the records of the Prussian and Russian Empires, which at some point mandated records to be in German (old script) and Russian, respectively. As the 19th Century progressed, so did a sentiment of nationalism for both the Polish and Ukrainian priest. The Polish priest might have started to include Polish words and the Ukrainian priest include Ukrainian words in the vital records. First Names or Common NamesThese were usually in Latin. Sometimes Polish or Ukrainian was given. This may be strange since these people never went by their Latin equivalent! First names are very important to the genealogist. It’s imperative to keep track of all official names, as well as unofficial nicknames. It’s clear that "Uncle Mike" is probably referred to as "Michael" on his birth, marriage, and death record. This important feature, however, in our Eastern Galician/Western Ukrainian research can become even more complex. We may have for one person various forms of a simple

first name. We may find his name: This point is expounded on by Polish and Ukrainian intense system of "nicknames", or as they are known grammatically-"diminutives". As for records, before 1772 or so, you’ll more than likely find the name in Polish, Latin or Old Church Slavic. After that date through World War I, you’ll usually find only the Latin. Sometimes, Polish will be used. Also, Ukrainian may be used alone or along with the Polish or Latin. Obviously, it’s critical to the genealogist to note names correctly in our reports, either on paper family group sheets and pedigrees or in a genealogical software program. (I prefer using a genealogical software program for many reasons. A Little GrammarPolish and Ukrainian are inflected languages. This means that words undergo a change in form to indicate their grammatical function. Of course, the more vocabulary and better understanding of grammar you have, the easier it is to read documents. The scope of Polish/Ukrainian grammar is much too complex for this site. However, one need not be fluent in these languages to understand the basics of these various word endings as they pertain to reading vital records. One MUST, however, be aware that such changes exist and occur frequently. No one should feel that he/she can not trace Galician roots because of the lack of fluency. The two most popular cases (or grammatical forms) are Nominative and Genitive. The Nominative case is the subject of the sentence. This case is always used to show a name in its most basic form. On vital records, the subject of the record (the person born, married or died) will be in the Nominative case. The Genitive case shows possession. The first name in each sentence is in the Nominative case while the Genitive case is bolded in the following examples:

You can see on the one hand how it can get tricky and on the other hand how important such a grammatical feature is. Be Careful: Studying the sentence careful is very necessary! Until you get comfortable with the Latin, Polish and Ukrainian names and grammar, read very carefully! When you see the name Franciszka, you may

think quickly that this is the girl's name which translates into English as

Frances. However, if you read the sentence "Piotr, syn Franciszka i Anny",

you'll see that Franciszka is actually the genitive case of the name Franciszek,

which is very much a man's name (and translates into English as Francis).

This occurs quite often since the common grammatical ending for the genitive

case for masculine names is the ending -a, which would then "appear" to

look like a feminine name. Other such examples:

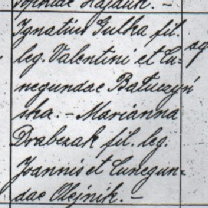

(Latin: Ignatius Gulka fil. leg. Valentini et Cunegundae Bałuczyńska. Marianna Drabczak fil. leg. Joannis et Cunegundae Olejnik.) (Translation using Polish first names: Ignacy Gulka, legitimate son of Walęty and Kunegunda Bałuczyńska. Marianna Drabczak, legitimate daughter of Jan and Kunegunda Olejnik.) (Trans. using Ukrainian first names: Ihnat Gulka, legitimate son of Valentii and Kunehunda Baluczynska. Mar'iana Drabczak, legitimate daughter of Ivan and Kunehunda Olejnik.)

From the table below, you can see some more

examples. Although you'll see the predominate Genitive ending in Polish

and Ukrainian for masculine names is -a, and for feminine names is -y,

you'll see that there are exceptions to this rule.

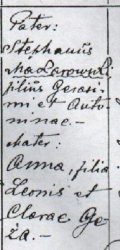

(Trans. using Polish first names: Father: Stefan Makarowski, son of Herasym and Antonina. Mother: Anna, daughter of Leon and Klara Geża.) (Trans. using Ukrainian first names: Father Stepan Makarowski, son of Herasym and Antonina. Mother: Hanna, daughter of Lev and Klara Geża)

Click here for a larger list of the more popular names illustrating these languages and grammatical endings. For a complete study of the subject on names, including a comprehensive list of names with their standard spellings, derivations, diminutives, name days for that name and equivalencies in Polish, Ukrainian and Latin, as well as Russian, German, Hebrew and others, you should consult the English language book First Names of the Polish Commonwealth: Origins and Meanings, written by William F. Hoffman and George W. Helon. Published in 1998 by the Polish Genealogical Society of America.

Last Names or SurnamesIn Slavic languages, e.g. Polish and Ukrainian, like many other languages, last names often show the difference between male and female.

Grammatically speaking, these endings are considered adjectives, so they form grammatical endings which include the distinction between masculine and feminine genders. For other surnames which end in consonants or "-o" or "-e", this same distinction may or may not be present. A possible -owna ending means that the woman is unmarried. An ending -owa means that the woman is married. Again, this may or may not be used. Jan Drabczak Marek Kawałko In Ukrainian, you may find the same thing with last names ending in -k or -enko. The proper feminine form for the last name Shevchuk and Shevchenko is the same as the masculine. However, you may find Shevchukova and Shevchenkova. In addition to changing endings for genders, these names can change endings depending on the role played in the grammar of the sentence. Helena Majewska, filia Petri et Annae Makarowskich The endings –ich and –ów is,

grammatically speaking, the genitive case plural. This case shows possession,

thus: It’s plural because it’s referenced back to BOTH Peter AND Anna. In singular, you could find:

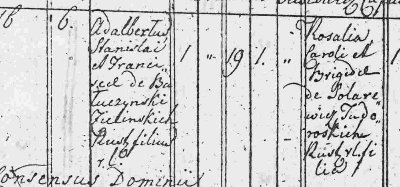

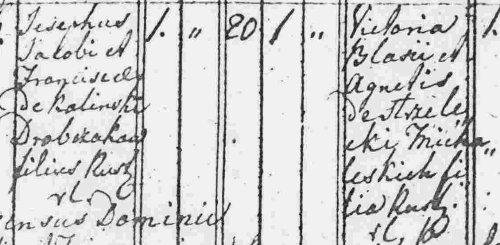

Table of Names: Languages and Grammatical Cases

Examples

AlphabetsPolish Alphabet

Note that the letter "ą"

is a separate letter from "a". Therefore, in proper Polish, “ą" follows AFTER

"a" in the alphabet and in alphabetical listings. This is most important when

reading gazetteers. "s" is sometimes written like a "f" When looking at English or other non-Polish documents, you may find the following occurrences. The Polish letter "ł" (which sounds like the English "w") is transcribed into English like an "l" or like a "w". You may find it as a "t" because a non-Polish speaking clerk mistook the "ł" to be a "t". The Polish nasal vowels "ą" and "ę" may be transcribed into English simply as "a" and "e". Or, "ą" may be "an", "on" or "am", "om". And "ę" may be "en" or "em". Examples: Lech Wałęsa is pronounced in

English as "Va-wen-sa" Ukrainian Alphabet

It’s written in the Cyrillic alphabet. (Although there was a movement in the 19th century to use the Polish alphabet and spelling rules as the basis.) If you know the Russian alphabet, note the following

important differences: For more language tricks played on Polish and Ukrainian spelling, visit my page on Passenger Lists. There I describe some various spellings one could use when searching for relatives in Passenger Lists (or any other English language resource). Transliteration Table and English Sound EquivalentsHere’s a transliteration table of Ukrainian letters and sounds into English and Polish spellings (sorted by Ukrainian alphabet):

*There are several standards of transliteration from the Cyrillic alphabet into English. I incorporate several of the derivations from the popular standards. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

www.halgal.com

Questions and Comments to Matthew

Bielawa |