Exciting New Publication: Ukrainian

Genealogy

by John D. Pihach

Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press, copyright

©2007

ISBN 1-894865-04-9 (bound); ISBN 1-894865-05-7 (paperback)

272 pages, about $34.95

Available through the internet:

http://www.amazon.com

http://www.utoronto.ca/cius/publications/books/ukrainiangenealogy.htm

John D. Pihach’s book Ukrainian Genealogy is the most

comprehensive and important book for Ukrainian genealogists available.

Pihach has successfully reined in the many aspects of Ukrainian genealogy into

one text. For the novice genealogist, he introduces the subject by

providing a background on the history of Ukraine and Ukrainian immigration to

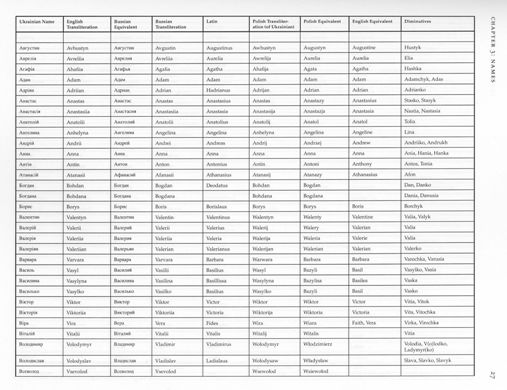

North America. He further covers the complex issue of language by

presenting a detailed, yet easy to read, account of Ukrainian given names and

surnames, as well as language usage as found in various documents important to

the genealogist. Although the book is subtitled “A Beginner’s Guide”,

Pihach provides an exhaustive study of maps, cadastral documents and a vast

collection of footnotes and citations that are sure to entice the experienced

researcher. The logical layout of the book allows it to serve as a trusty

reference to be returned to time and time again.

Pihach explains that the book is “a guide to tracing one’s

Ukrainian ancestry in Europe. It is not a guide for those wishing to trace

their roots on this continent…Consideration, however, is given here to those

North American records that are specifically Ukrainian or relate to the

immigrant experience”. Pihach presents North American records only in

relation to Ukrainian research in Europe or to determine one’s ancestral

village. This covers passenger lists, immigration records, naturalization

and citizenship records, census, homestead and land records, etc.

Pihach’s must read book is broken down into 12 chapters, 3

appendices, and an impressive bibliography. The first two chapters are an

introduction to Ukrainian genealogy. They deal with starting your

research, both in general genealogical practices as well as specific to

Ukrainian research. Pihach provides a brief history of Ukraine and of

Ukrainian immigration to North America. Furthermore, a history and

background of Ukrainian church records in Canada and the US can be found in

chapters 4 and 5. Due to a colorful past and complex terminology, the

subject of Ukrainian national, immigration and church history is not as easy as

one might think. Yet Pihach successfully gives the reader an excellent

overview, which serves the genealogist to better understand his/her own rich

national heritage, as well as to provide direction in terms of finding and

interpreting vital records and various other important resources.

An entire chapter is devoted to the singular, most

important task of the Ukrainian genealogist, that of locating the ancestral

home. Pihach, due to Ukraine’s rich history, must illustrate research

methodologies covering several countries and time periods: The Russian and

Austro-Hungarian Empires, as well as Poland, Hungary, Romania and the USSR.

Pihach goes into great detail explaining the geographic breakdown of the various

countries and time periods necessary to assist the researcher.

Furthermore, Pihach describes the array of invaluable gazetteers available.

Several

chapters of Pihach’s book are dedicated to vital records, the basis of most

family research. The book covers all the necessary aspects of vital

records. Pihach explains record keeping practices across national borders

and time periods. Furthermore, he explains the various availability and

location of records. Pihach has personally visited archives all across

Central and Eastern Europe. His intimate knowledge of the archives, as

well as their practices and catalogues, is a gift to all researchers.

Pihach includes a Ukrainian archive request letter writing guide and explains

the procedure for on-site archival visits in Ukraine. The author’s depth

of subject material is mind-boggling. In addition to writing about on-site

research, Pihach brings to light the availability of records and research

opportunities found on the internet. Pihach is completely abreast of the

most current information.

Several

chapters of Pihach’s book are dedicated to vital records, the basis of most

family research. The book covers all the necessary aspects of vital

records. Pihach explains record keeping practices across national borders

and time periods. Furthermore, he explains the various availability and

location of records. Pihach has personally visited archives all across

Central and Eastern Europe. His intimate knowledge of the archives, as

well as their practices and catalogues, is a gift to all researchers.

Pihach includes a Ukrainian archive request letter writing guide and explains

the procedure for on-site archival visits in Ukraine. The author’s depth

of subject material is mind-boggling. In addition to writing about on-site

research, Pihach brings to light the availability of records and research

opportunities found on the internet. Pihach is completely abreast of the

most current information.

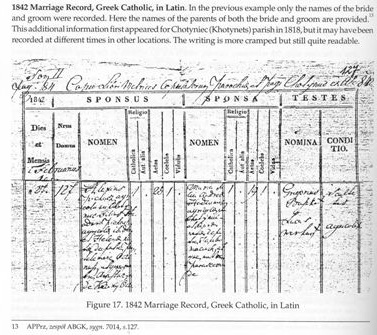

Pihach details the various types of vital records, both

Greek Catholic and Orthodox, both Austro-Hungarian and Russian Empire, both

Roman and Cyrillic alphabets. Pihach takes us on an exciting tour of

records from the late 18th to the 20th centuries giving

great detail in explaining the documents and provides a number of illustrated

examples. He translates the documents section by section providing a short

selection of common terms found in different languages, covering Ukrainian,

Russian, Latin, Polish, German and Romanian…(who says Ukrainian research isn’t

fun?).

As every genealogist knows, there’s more to research than

vital records. Since the break-up of the Soviet Union and fall of

Communism in the early 1990’s, new documents have only recently become

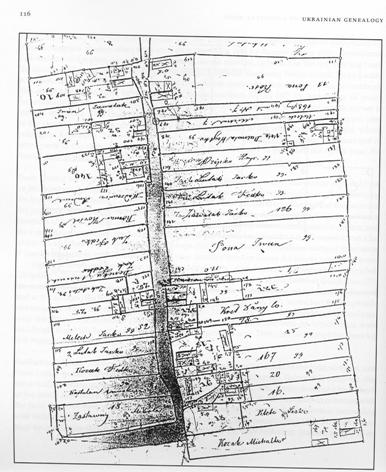

available. One of the most important features of the book is the entire

chapter on Austrian land records. Pihach writes: “When Austria acquired

Galicia, in order to establish a reliable basis for land taxation the

authorities initiated land and tax reforms that required the measurement of all

land properties in the new crownland.” Pihach explains the 19th

Century documents which serve as a complete picture of a village, a snapshot in

time.

Pihach

also writes about the many types of maps available for research. He

illustrates over a dozen of the most popular and informative maps by featuring

the village Chotyniec, located on the Polish-Ukrainian border. By using

the one village as an example, Pihach is able to go into great detail about each

of the map series. Included in the study is an in-depth discussion of the

cadastral maps and associated texts, an exciting feature of Austro-Hungarian

research. The maps and texts, created for taxation purposes and settling

property disputes, allow the researcher to reconstruct the ancestral community.

Pihach writes: “…literature about cadastral surveys and maps in English is

scarce”. Pihach fills the gap by bringing to light this incredible

resource.

Pihach

also writes about the many types of maps available for research. He

illustrates over a dozen of the most popular and informative maps by featuring

the village Chotyniec, located on the Polish-Ukrainian border. By using

the one village as an example, Pihach is able to go into great detail about each

of the map series. Included in the study is an in-depth discussion of the

cadastral maps and associated texts, an exciting feature of Austro-Hungarian

research. The maps and texts, created for taxation purposes and settling

property disputes, allow the researcher to reconstruct the ancestral community.

Pihach writes: “…literature about cadastral surveys and maps in English is

scarce”. Pihach fills the gap by bringing to light this incredible

resource.

In

addition to a complete list of essential archive addresses (covering Canada, US,

Ukraine, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Russia and Romania), the book contains three

appendices. The first, “Languages”, covers several alphabets, including

Ukrainian and Russian (along with various transliteration systems), Church

Slavonic, Polish, German and Romanian. Examples of cursive writing are

also included to help with interpreting records. The second appendix gives

contact information on other ethnic groups located in Ukrainian territories,

such as Polish, Jewish, German, Mennonite, Rusyn (aka Carpatho-Rusyn), Czech,

Slovak and Russian groups. The last appendix lists useful web sites.

This last subject is a challenge for publications in print since web sites often

come and go. But Pihach careful chooses the most essential and informative

internet sites. Finally, an exhaustive bibliography, 12 pages worth, is

provided. The bibliography is broken down by category making it easy to

follow and reference. These last two sections are sure to keep the

genealogist busy…and well informed!

In

addition to a complete list of essential archive addresses (covering Canada, US,

Ukraine, Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Russia and Romania), the book contains three

appendices. The first, “Languages”, covers several alphabets, including

Ukrainian and Russian (along with various transliteration systems), Church

Slavonic, Polish, German and Romanian. Examples of cursive writing are

also included to help with interpreting records. The second appendix gives

contact information on other ethnic groups located in Ukrainian territories,

such as Polish, Jewish, German, Mennonite, Rusyn (aka Carpatho-Rusyn), Czech,

Slovak and Russian groups. The last appendix lists useful web sites.

This last subject is a challenge for publications in print since web sites often

come and go. But Pihach careful chooses the most essential and informative

internet sites. Finally, an exhaustive bibliography, 12 pages worth, is

provided. The bibliography is broken down by category making it easy to

follow and reference. These last two sections are sure to keep the

genealogist busy…and well informed!

I strongly urge everyone researching, or on the verge of

starting to research, his/her Ukrainian roots to run, not walk, to get a copy of

this book! Pihach has managed to bring all components of Ukrainian

genealogical research into one book. I’m confident that every genealogist

will refer to this book over and over again.